What is fantasy and where do my books fit in?

Your books are categorized for sale as fantasy, but you don’t have magic, no dragons, no creatures or other beings of any kind? What gives?

Yes, my friend, that is correct. And I’ll tell you a secret: I wish I didn’t HAVE to categorize my books as fantasy. If it was up to me, I’d just call them fiction and be done with it. But the market is the market, and markets require categories within categories for selling things. The better your books breaks down into a subgenre, the easier it is to sell.

So how did my books end up in fantasy? That answer requires a history lesson. This will take a bit, so go grab a cup of coffee or tea, some cookies (or my favorite… a giant piece of chocolate cake), then come back and get comfortable.

Back already? Is it a big cup of coffee or tea? Okay, good. Let’s begin.

You loved Game of Thrones. You’ve read all the latest by K.F. Breene, Brandon Sanderson, and George R. R. Martin. You play video games and can cast a spell with the best of them. So if a book has a dragon on the cover and descriptions about mages and dark magic, you’re all in. But did you know these kinds of books meet a fairly modern definition of fantasy?

In truth, modern fantasy has a very small family tree, and it’s not that old. The root of the whole plant comes from a handful of branches. Certainly, legends and myths of old could be classified as fantasy, but modern genre fantasy differs from classical myths, legends, and fairytales in several ways.

Modern fantasy postulates a different reality, either a fantasy world separated from ours, or a hidden fantasy side of our own world. In addition, the rules, geography, history, etc. of this world tend to be defined, even if they are not described outright. Traditional fantastic tales take place in our world, often in the past or in far off, unknown places. It seldom describes the place or the time with any precision, often saying simply that it happened “long ago and far away.” (Star Wars, anyone? A saga written with ancient myths and legends in mind.)

The second difference is that the supernatural in fantasy is by design fictitious. In traditional tales, the degree to which the author considered the supernatural to be real can span the spectrum from legends taken as reality, to myths understood as describing in understandable terms more complicated reality, to late, intentionally fictitious literary works.

Finally, the fantastic worlds of modern fantasy are created by an author often using traditional elements, but usually in a novel arrangement and with an individual interpretation (not based on a cultural understanding). Traditional tales with fantasy elements used familiar myths and folklore, and any differences from tradition were considered variations on a theme; the traditional tales were never intended to be separate from the local supernatural folklore. Transitions between the traditional and modern modes of fantastic literature are evident in early Gothic novels, the ghost stories in vogue in the 19th century, and Romantic novels, all of which used extensively traditional fantastic motifs, but subjected them to authors’ concepts.

A lot happened in the centuries leading up to the modern era. Each age had its own impact on the development of modern fantasy, from the Enlightenment and its Romanticism onward, but we’ll fast forward.

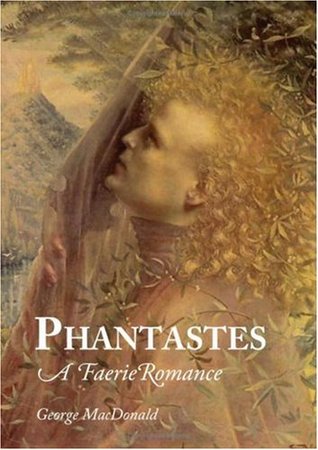

George MacDonald published Phantastes in 1858, arguably becoming the first explicitly fantastic work of literature. Many authors throughout the Victorian and first world wars wrote works in this same vein of fantasy, but the genre didn’t really come into its own until nearly one hundred years after MacDonald when J.R.R. Tolkien published The Lord of the Rings, firmly establishing the genre of fantasy as commercially distinct and viable from other forms.

It is difficult to overstate the impact that The Lord of the Rings (hereafter LOTR) had on the fantasy genre; in some respects, it swamped all the works of fantasy that had been written before it, and it unquestionably created “fantasy” as a marketing category. As a result of its huge mainstream acclaim, authors who came after would go on to create an enormous number of Tolkienesque works, using the themes found in LOTR. This was the birth of what we now call epic fantasy.

With the immense success of Tolkien’s works, publishers began to search for a new series with similar mass-market appeal. It wasn’t until 1977’s The Sword of Shannara that publishers found the sort of breakthrough success they had hoped for. The book became the first fantasy novel to appear on, and eventually top the New York Times bestseller list. As a result, the genre saw a boom in the number of titles published. By the early 1980s the fantasy market and has since become increasingly intertwined with mainstream fiction.

Readers have bought into fantasy, hook, line, and sinker. In recent decades, subgenres proliferated, and it’s become difficult to lump all works of fantasy into one, small definition.

Sounds great. But Stephanie, is there one theme in common amongst all subgenres of fantasy though? I mean, saying “subgenres proliferated” is kind of a word nerd’s way of creating a loophole.

Why yes, I’m glad you asked! The fantasy genre, as a whole, is recognized primarily for its fictional worlds and universes. My books have a completely, 100% fictional setting. Any specific variations from this basic starting point—whether there are elements of magic, creatures, goblins, or beings who control the elements of the earth, etc.—have more to do with specialization and subcategories more than anything else. At it’s root, fantasy needs to be fictional.

And that’s where my books come in.

To say my books are square pegs trying to fit into round holes is both an understatement and apt. Publishers didn’t know what to do with JK Rowling’s Harry Potter books at first. Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series crossed genres that caused some to scratch their heads. But there are always firsts. Someone is always going to write something that doesn’t quite fit anywhere. Whether or not others will follow that path remains to be seen.

I’ve been explaining the development of modern fantasy throughout this whole article. And while I do categorize my novels as fantasy, my work actually comes from a different tree altogether.

Wait, is this a bait and switch?

Yes, and no. But mostly no. I loved LOTR, I enjoyed reading the first several books of the Game of Thrones series. But my books don’t necessarily harken to that kind of fantasy. I draw inspiration first and primarily from history and historical fiction. My Crowns of Destiny series plays out more like book of historical fiction. The setting is heavily inspired by medieval Europe. There are no fantastical elements modern readers might recognize, but that doesn’t mean the books aren’t fantasy. They are 100% fictional. Like traditional myths and legends of old, I write settings that could be in our world (or very much like our own world), but just exist in some unknown place. If I’d been writing before the age of exploration, this could easily be true. And at the same time, entirely fantastical!

And yet, unlike traditional myths and legends, the rules, geography, history, of my world is defined, though all the rules are not described outright. Much of it will feel familiar to those who read historical fiction, harkening back to its true root in historical fiction. Authentic settings and technology, medicine, and ways of life match those from history books. Put another way, the books have a historic setting but without restraints of real world’s history and geography.

As I move into a new project, I’m adding a few more elements of fantasy. I’ll be using elements of the fantastical in the form of creatures and the supernatural much more similar to magical realism than fantasy. At least once those books are published, I likely won’t have any need to explain genre. I look forward to that day!

So where DO my books fit in?

They really don’t fit anywhere, to be honest. Square peg. Round hole. There just isn’t really anything else like them (and believe me, I’ve looked!). So I had to categorize them for sale the best I could, even if there was no perfect fit. And it’s a shame too, because I think they are really good stories! I think there are a lot of stories out there that fall through the cracks due to a category or label.

Would I go back and redo things if I’d known how hard it would be to categorize? Would I add magic? No, probably not. Because that wouldn’t be true to who I am as a writer or true to what my story was meant to be. Why throw in some magic just as a tribute to a category, or because it’s “supposed to be there”? I’m afraid I’m not very good at doing something “just because” or to please others. I never set out to fit into a competitive commercial market. I simply set out to write the stories on my heart, and that’s what I’ve done. The fact that the stories on my heart don’t fit a specific or currently accepted marketing genre just means my stories are as unique as I am. And I’m okay with that! It’s the main reason I’m an indie author. Agents and publishers knew the books would be tough to market.

If you are a reader, I challenge you to try something different, something outside your normal genre. You might find a gem. If you are an author, stretch yourself. Try to write a twist on an accepted genre. And if you are an aspiring writer, write the story that’s on your heart. Stay true to who you are.

The Scribe’s Daughter is not an easy book to categorize. It takes place in another world, but the reader will encounter no dragons or vampires. Its major female character is in her teens, but her story will appeal to readers of all ages. Kassia’s life could easily be rooted in the Middle Ages, but it isn’t. It is simply a very well written book about a character that readers will care about, amused by her dry humor, admiring her courage, and wincing at her recklessness.

Sharon Kay Penman

Disclaimer: I have to acknowledge that a great deal of the material for this article comes directly from here.

One Comment

Robert Southworth

Interesting read. Thank you.