Šarru-kēn – Empire Builder

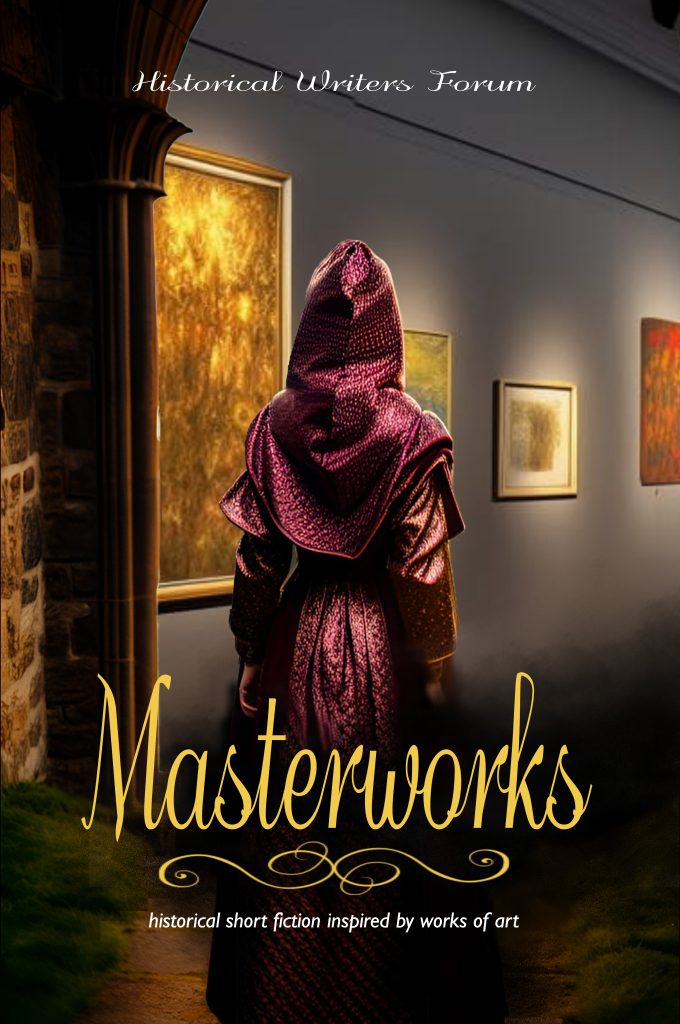

The Historical Writers Forum releases its third anthology of short stories on November 1, 2023. This newest anthology, titled Masterworks, tells stories inspired by works of art. Because of my research into ancient Sumeria, I knew I wanted to tell a tale set in this intriguing era. Many people will be familiar with the name Sargon of Akkad, or at the very least, the Akkadian Empire. This fascinating man is the main character of this time period which is the stage for my story.

While my short story was inspired by a musical instrument, I wanted to start off the celebration of this anthology by introducing readers to the man, the myth, the legend behind the era. Cheesy cliche, I know, but in the case of Sargon of Akkad, it’s quite literal.

While we know the name Sargon today thanks to the Hebrew form as written in the biblical record in I Kings (another Sargon, Sargon II), his Akkadian name, Šarru-kēn, how his own people would have referred to him. It was not his birth name, but a name he acquired after taking the throne. It meant “legitimate king” in Semitic.

Much like other legends more familiar to us today, like King Arthur or Grimm’s fairy tales, the mythology surrounding Sargon of Akkad grew and changed with the passing of time. The Sumerians themselves would have known a very different man from the legend he would become, for legends usually only contain a grain of truth. Subsequent empires would take the Sargon legend, adding their own flavors- Amorites, Assyrians, and finally the Babylonians, who codified the most formal changes to those myths and legends. And because we have so much of the Babylonian record, what we know of Sargon today is mostly influenced by these sources. This thick fog of history makes it difficult to separate the myth from the man.

Starting during the Uruk period (c. 4100–2900 BC) and until Sargon’s time, the lands of Sumeria were mostly city-states, each city ruled by an ensi. Over this thousand-year period, the population grew, and the people settled areas of the region competed for resources. (See my earlier blog posts for more information on the history of Sumer before 2300.)

Around the time of Sargon’s birth, the cities of Umma and Lagash had been engaged in a bitter, 100-year war. Lagash had come out on the other side so diminished the citizens faced stifling taxes and significantly restricted personal freedoms. Urukagina inherited a mess when he took the throne of Lagash. He instituted a multitude of reforms, creating a rudimentary code of law, and tried to improve the lives of the citizenry.

Around 2340 BC, the culmination of the wars between Umma and Lagash would occur when a man named Lugalzagesi sacked and burned the city of Lagash, destroying its temples and taking Urukagina captive. Urukagina ultimately survived, and it is thanks to his scribes we have the Lagash version of the events. Lugalzagesi conquered more cities, though scholars aren’t certain if he intended conquest or merely the acquisition of plunder. The latter seems the most likely.

Fortunately, another, stronger leader put an end to his rampage.

The man who would later crush Lugalzagesi’s combined kingdoms of Kish, Lagash, Larsa, Nippur, Ur, and Uruk came from uncertain origins. Depending on which mythos you read, he was an outsider of Semitic background, possibly the adopted son of the Kish king Ur-Zababa’s gardener, though this version of his history comes from later legend rather than any evidence from his own time. What we know of his earliest days before conquest comes from The Sumerian Kings List, a record compiled not long after the Akkadian kings, which states that Sargon was, if the list is to be believed, a gardener eventually becoming the cupbearer of Ur-Zababa, king of Kish.

The story takes its most interesting turn when Ur-Zababa, the ensi of Kish disappears from the historical record. There are a few likely explanations for this. Either Sargon, as Ur-Zababa’s right-hand man, decided it was time to seize power for himself, or else Lugalzagesi intended Kish to be a part of his conquest and him. Most scholars seem to think Lugalzagesi is the culprit.

If indeed Lugalzagesi had been the agent of Ur-Zababa’s death, Sargon took it upon himself to seek vengeance on behalf of his old master. Who knows if Lugalzagesi had any reason to believe the old king’s cupbearer was an ambitious military genius? He would soon find out.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)

There was no set order of succession to any throne. Even a ruler’s offspring would have to fight to take their father’s throne. Therefore, the emptying of any throne created a vacuum of power, chaos, and a considerable amount of terror for the average citizens of any city. We don’t know if others vied for this position, but we know for certain Sargon did.

He had been very popular in Kish, and with this network of support, he seized the throne. His first goal became to hunt down Lugalzagesi (either out of a sense of rivalry or as a personal vendetta to punish his former master’s killer) and remove him from power. Pulling together an army, Sargon ventured first to Lugalzagesi’s capital, Uruk, and “smote it,” destroying its walls. The defenders fled, obtaining reinforcements-fifty ensis from the surrounding cities-to help them. They took their stand against the pursuing Sargon and were defeated. It was only at this point the absent Lugalzagesi returned to his capital, walking into the defeat of his army, the downfall of his city, and was himself captured.

Sargon took Lugalzagesi in a neck stock to Nippur where, at the Enlil gate of that great city, he left the former invader to sit, becoming a laughingstock of the citizenry.

After leaving Nippur, Sargon went back south where Lugalzagesi’s supporters still had hopes of stopping Sargon. He attacked Ur, then continued to the region between Lagash and the Persian Gulf where, legend says, he washed his sword in a ritual commemorating his victories. After leaving the Persian Gulf, he destroyed Umma, finishing his conquest of the south.

From this point, he went west and north, then east. After this, the inscriptions created by scribes in Nippur during Sargon’s own reign, end. According to later records, Sargon returned to his city of Agade, and it was likely at this point his daughter, the future Enheduanna, was born to his wife Tashlultum.

Over the course of his fifty-year reign, Sargon would set up the world’s largest first empire, administrated out of his capital city, Agade/Akkad. By appointing loyal friends and family members to key positions in cities across the region and installing garrisons in far-flung outposts, he was able to create a network of support across the diverse region. Of his huge court of officials and soldiers at home, Sargon boasted that “5400 men ate bread daily” before him. During his reign, Agade became the most splendid, wealthy, and resplendent cities of the ancient world. Gifts and tributes came to him from all over the known world. Ships brought goods in from regions as far away as India, Egypt, and Ethiopia.

After his fifty-year reign, His sons (possibly twins) Rimush and Manishtushu each followed him. And while they kept their father’s lands intact despite an increasing number of rebellions, having to reconquer much of the land their father had taken again and again, they never maintained the same golden age Sargon reigned over.

Manishtushu’s son, Naram-Sin, was probably the greatest king after Sargon, but he was also the last of the Akkadians to rule before the land was invaded by the Gutians, a people from the Zagros Mountains (modern Iran). They would rule the lands of Sumer for the next 50 years before the dawn of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur (known to historians as Ur III), then eventually the Amorites who struggled with the cities of Isin and Larsa (the Isin-Larsa period). Next would come the Amorite Hammurabi, followed by Assyria and then Babylon.

Please click here for a list of works consulted.