Enheduanna as Priestess

available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain.

“The compiler of the tablets was Enheduanna. My king, something has been created that no one has created before.”

The Temple Hymns 543-544

A man whose birth story is lost in the sands of time. Mythology says he was fished out of the river from a reed basket by a gardener in Kish who adopted him. He would become the cupbearer to a king. Eventually, he would sit on the throne of that very same king.

Sargon of Akkad. He is one of the most familiar names to those who study ancient Mesopotamian history. But the story of his daughter is almost more intriguing to me.

Because of the time and place of her birth, her parentage, and the advantages of those situations, she was placed in such a strategic way that she would go on to leave her mark on history in ways we are only now beginning to appreciate.

Meet Enheduanna.

She lived in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC in “the land between the rivers,” modern-day Iraq. We don’t know the name her parents gave to her at birth. History only records the name Enheduanna, the title received upon her appointment as en of Ningal’s temple in Ur.

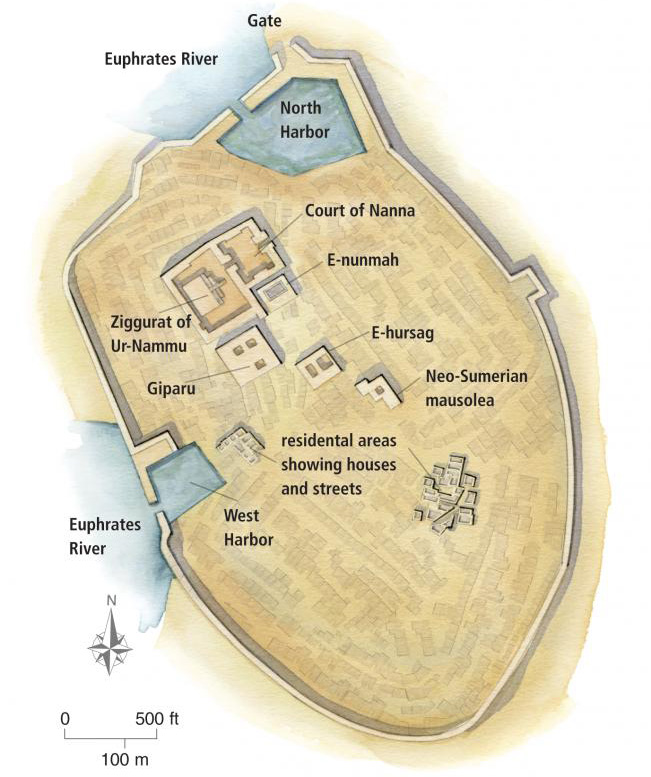

Ur was a significant port city on the Persian Gulf, where the Tigris and Euphrates River met and emptied into the gulf. It began, most likely, as a small village in the Ubaid Period of Mesopotamian history (5000-4100 BC) and was an established city by 3800 BC. In its time, Ur was a city of enormous size and affluence which drew its vast wealth from its position along said water courses and the trade this allowed with countries as far away as India. Archaeological excavations have revealed that the citizens enjoyed a level of comfort unknown in other Mesopotamian cities.

Temple Hymn 8 refers to Ur as the “first-fruit-eater of all lands” and “An’s first piece of earth.” This implies that Ur is the city of the first gods. Through conquest, Sargon*, Enheduanna’s father, had become the ruler of a diverse land: Semitic in the north and Sumerian in the south. Such a vast territory could only be unruly, and he needed help to contain and control it. The Sumerian’s impressive culture rested on the beliefs and rituals centered in their relationship to the natural world. This relationship formed their ritual year which centered on the moon’s cycles. In the minds of the Sumerians, the moon god Nanna, son of An, was set apart from the other gods, making moon time fundamental to the structure of their lives and culture.

Sargon used this to his advantage. To combat the antagonism and sometimes open rebellion of the southern Sumerian cities, he chose the moon god’s temple at Ur as the place to send his daughter. His appointment respected the Sumerian cultural tradition while also placing his Semitic stamp on the southerners’ religious system.

After her appointment, Enheduanna would have traveled to her new home in Ur, a journey that would have taken several days either by boat or barge, south from her father’s city of Akkad, on the Euphrates River. While Akkad was a fairly new city, either built by Sargon or chosen by him to be the seat of his new power, Ur could only have over-awed in both size and splendor.

Once Enheduanna had settled in, Nanna would have required much preparation for her. First, she had to be “chosen” by the god himself. The selection process would most likely have been conducted via divination by the most prominent seers who spent hours studying the internal organs of sheep and studying the stars. Assuming everything went well (and how would it not when one’s own king has selected his own daughter for the office?) the daughter of Sargon was officially chosen for this most esteemed office. She was now no longer owned her birth name. She was now Enheduanna.

The name is symbolic: En referred to her role as high priestess. Hedu meant ornament, and Ana referred to heaven (or concurrently, the god Anu). The literal translation put together means “High priestess, ornament of heaven” but could also mean “The high priestess of An (the sky god).”

In her poetry, she called herself nin-dinger, godly lady. While there may have been priestesses in Ur before her, Enheduanna virtually created the office of the en, or high priestess, during her tenure.

Why was the selection of the en so important?

The high priestess would become the physical representation of Ningal, the moon goddess and Nanna’s wife, and would play Ningal’s role in the annual sacred marriage celebration. This marital union of Ningal and Nanna ended the festivities and served as the culmination of the celebration. It ensured a bounteous harvest, fertile livestock, and prosperity for the people.

What was her installation ceremony like?

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

What we know of the ceremony comes from a seal created in Enheduanna’s own lifetime. Found in the gipar in 1927 by Sir Leonard Woolley, the calcite disk, 25 cm in diameters and 7 cm thick, displayed the image of a woman during a ceremony on its front. The inscription on the back of the seal was nearly complete, but because it had been broken at the bottom, the end was missing. Fortunately, some 500 years after its creation, a scribe of the Old Babylonian era thought to use the seal’s inscription to fill space on the bottom of his own, unrelated tablet. It was thanks to this scribe we have the complete text.

The front of this seal shows Enheduanna facing an early ziggurat, accompanied by a clean-shaven and robe-wearing priest who carries a spouted jug without a handle and pours from it onto an altar. A third priest carries a wand which was used for ceremonial sprinkling, and a third carries a bucket.

Enheduanna wears a robe with long flounces common to this era and the thick hairband of office. Her hair is worn long and falling down her back with some braided at the sides.

Where did Enheduanna live?

The name of Nanna’s temple, Ekishnugal, relates to alabaster, a color similar to the white light of the moon. It was in this temple complex that the high priestesses were the central figures. Within this temple complex, Enheduanna lived for the almost forty years of her tenure as high priestess.

(The years she didn’t live in the temple complex is the subject for an upcoming blog post!)

The residence of the en was called the gipar. From archaeological evidence, we know that the gipar Enheduanna occupied sat very close to Nanna’s temple. It comprised three buildings: the temple of Ningal built around a courtyard, like most traditional houses of that era; the gipar proper, the building Enheduanna made her personal home; and a private chapel for the high priestess’ own use. A wall enclosed all these buildings.

What did Enheduanna do every day?

The duties of the en focused primarily on the care and nurturing of Ningal in the temple. A statue of the goddess stood on a platform in the center of the room in a private cella in the very center of the temple. Stairs led up to the statue where she could be easily reached, enabling her worship and access to feed and clothe her. The daily care and nurturing of Ningal ensured the goddess’ well-being, which ensured the prosperity of the people of Ur.

Another, larger room of the temple called the e-nun (“house of the queen”) held a large, low platform which, historians have surmised, was used as Ningal’s bed, a key element during the annual sacred marriage ceremony.

Besides filling one of the most influential religious roles in the country, the high priestess in Nanna’s temple inherited the important role of reckoning time. The calendar and all that it implied-the seasons, the designations of planting and harvest, the festivals connected to agriculture and religious beliefs-were calculated by the position of the moon in its cycle. The high priestess, steeped in the knowledge of the movements of nature’s elements, kept track of the moon’s phases, along with other astronomical observations. And thus, the high priestess maintained order. Her connection to the divinity made her the intermediary between earth and heaven, allowing her to maintain the proper observances that pleased the gods.

What is Enheduanna’s legacy?

If Sargon’s primary role for his daughter was merely to unite the varying cultural factions of his new empire, he could not foresee when he appointed her that she would go on to serve as one of the most effective and fruitful high priestess in the history of Ekishnugal. In the forty years she served, she produced the world’s first attributed poetry. Her “Temple Hymns,” a series of 42 hymns listing each of the temples of Sumer, city by city, praised the various gods and goddesses from each city, drawing them in and connecting them neatly under one unified religious system for Sargon’s new empire.

But her poetry didn’t just help the new Akkadian ruler wrestle a rebellious people to his throne. Her writing inspired the people of the “land between the rivers” for millennia afterwards.

“[Enheduanna] is credited with creating the paradigms of poetry, psalms, and prayers used throughout the ancient world… Her compositions, though only rediscovered in modern times, remained models of petitionary prayer for even longer. Through the Babylonians, they influenced and inspired the prayers and psalms of the Hebrew Bible and the Homeric hymns of Greece. Through them, faint echoes of Enheduanna, the first named literary author in history, can even be heard in the hymnody of the early Christian church.”

(Paul Kriwaczek from Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization)

*While Sargon is his more familiar name, Šarru-ukīn was his Akkadian name. The name Sargon first appears in the historical record in the biblical book of I Kings which refers to a king with the same Akkadian name: Sargon II, who was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, born in 762 BC.

Information for this article comes from Betty De Shong Meador’s gem of a book, Princess, Priestess, Poet: The Sumerian Temple Hymns of Enheduanna. University of Texas Press, 2010.